Another Internet Shutdown in Sudan: The Actual Cost of Weaponizing Internet Access by the African Gov't

Internet penetration in Africa remains the lowest globally, as only four in every ten persons in the continent had access to the internet as of December 2021. Moreover, the online penetration rate on the continent was below the global average, measured at around 66 percent. Nevertheless, according to Statista forecasts, the number of internet users in Africa will increase to approximately 565 million in 2022, six times more than in 2010. By 2025, the figure might come close to 700 million.

However, governments across the continent have repeatedly weaponized access to the internet in their respective countries at the slightest provocations. This might not be unconnected with the continent’s several decades of military rules, where the constitutions were arbitrarily suspended and human rights trampled upon by the military jack booths. A clear violation of freedom of expression and access to information rights to limit the free flow of information online and news coverage of incidents on the ground, throwing the continent’s hard-earned democracy to the dogs.

Again, Sudan shut down internet service in the country yesterday as tens of thousands of Sudanese gathered in the capital city of Khartoum to protest the October military Coup, which led to the forced resignation of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

Activists called for mass protests to mark the third anniversary of massive demonstrations that led to the overthrow of the autocratic ruler, Omar al-Bashir, in an uprising that paved the way for a power-sharing arrangement between civilian groups and the military. So far, about seven protesters have been reportedly shot dead as huge crowds staged rallies in the capital and other major cities across the nation.

Confirming the suspension of the internet, staff at Sudan’s two private sector telecom companies told the Reuters news agency that orders to shut down the internet came from authorities.

Earlier in the day, security forces closed bridges between the capital and its two sister cities and fired large amounts of tear gas at the gathering crowds, witnesses reported. Civilians pushed back using stones to barricade key entry and exit points throughout the city.

“June 30 is our way to bring down the coup and block the path of any fake alternatives,” said the Forces for Freedom and Change, an alliance of civilian groups whose leaders were ousted in the coup.

Demonstrators also took to the streets earlier in June to demand justice for pro-democracy protesters killed by authorities in 2019.

A UN special representative earlier this week called on security forces to exercise restraint. “Violence against protesters will not be tolerated,” Volker Perthes said in a statement.

Sudan’s Foreign Ministry was critical of Perthes’ comments, saying they were built on “assumptions” and “contradict his role as facilitator” in the dialogue between the country’s military leadership and civilian groups.

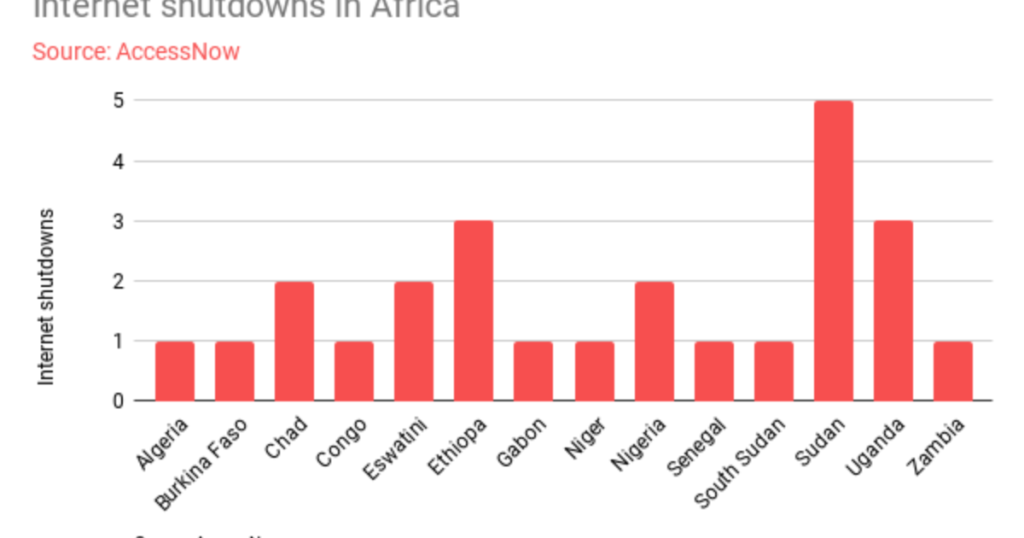

History of internet shutdowns in Africa in recent years

Although it is now a yearly ritual for the Sudanese, their government isn’t alone in this act of suppressing their people’s voices through internet disruptions, including shutdowns and social media restrictions.

In 2018, the Sudanese government cut off access to the internet for 68 consecutive days from 21 December 2018 up until February 26, 2019. The Sudanese government did this to quell protests, resulting in the military coup the following year.

Massive protests began after the government decided to triple the price of goods when the country was suffering an acute shortage of foreign currency and inflation of 70 percent. Another reason for the protests was the refusal of President al-Bashir to step down after being in power for 30 years. Another shutdown from 3rd June to 9 July 2019 (36 days) cost the country as much as $2 billion.

Also, another month-long internet shutdown occurred on October 25, 2021, when another military coup deposed Hamdok. Again, as citizens took to the streets in protest of Hamdok’s deposition, the Sudanese authorities shut down access to internet and telecommunication services.

In October 2020, Tanzania restricted access to the internet and social media during elections. In addition, Ethiopia imposed an internet shutdown which lasted for close to a month in June 2020, after unrest that followed the killing of a prominent Oromo singer and activist, Hachalu Hundessa. Also, in November 2020, Ethiopia blocked access to the internet in the Tigray region after prime minister Abiy Ahmed ordered a military offensive on the breakaway area.

Zimbabwe, Togo, Burundi, Chad, Mali, and Guinea will also restrict access to the internet or social media applications sometime in 2020. Nigeria also shut down access to Twitter after the platform deleted President Buhari’s tweet that violated its policies. In 2011, the Egyptian government cut internet access, ostensibly to prevent people from coordinating protests through social media.

Eswatini (Swaziland), an African country that practices a monarchical system of government, also asked mobile operators such as MTN to block access to Facebook and Facebook Messenger as anti-government protests raged.

Counting the Cost

In the last four years, 32 African countries, including Nigeria, Uganda, and Ethiopia, have experienced internet shutdowns for politically-motivated reasons. It cost the continent over $2 billion, but the cost could be more severe for Sudan. The country is barely recovering from a 30-year isolation period where international sanctions prevented foreign trade or investment.

Any tinkering with the internet service affects both the macro and the microeconomic growth of a nation, particularly the startups, who rely heavily on the internet service to carry out their day-to-day operations.

Data shows that 759 days (18,225 hours) of internet disruptions cost the global economy a staggering $8.05bn in 2019, and Sub-Saharan African countries lost about $2.16bn.

According to NetBlocks, a watchdog organization that tracks cyber-security and internet administration, each day of the Twitter ban costs Nigeria about N2.18 billion.